Exploring Fairy Tales: My Father's Legacy

In our old home, at Ibn Hawqal street, in Zizinia, Alexandria, less than a mile from the Mediterranean, I could distinguish the scent of each color.

Green smelled of lavender, the perfume Mother used around the house. She insisted on buying me a new bottle whenever I visited each summer, long after I had moved on from the family scent and succumbed to brands advertised for by strangers I would never meet. Lavender made me feel like I still lived in Ibn Hawqal street, named after the 10th century Arab traveler and geographer, Ibn Hawqal al-Bughdadi. He was among the first to draw a map of Sicily and Alexandria in Arabic. The street is in Zizinia, a neighborhood named after the Alexandrian-Greek Count Stefanos Zizinia, a 19th century cotton tradesman turned diplomat. His lands once hosted the electric tram lines that still run today, and his palace was bombed by the British colonial artillery.

Blue should have smelled of the sea, but it smelled like my father’s old paintings of the sea in Glymonopolo, a mile west of Zizinia. More accurately, blue smelled of paintbrushes and paint left drying on his painted canvases.

Yellow smelled of old pages from the children’s storybooks he co-authored and illustrated 50 and 60 years ago. He had kept them neatly in large folders. I have given up trying to be as well organized as he was. Or as good with my hands. He framed all his paintings himself. He looked at me as he showed me where he kept all the stories. He was smiling. He was always smiling when he talked about his art.

Red smelled of my imagination as I would read his work, almost twenty years after the last book was published. They must have already felt like history for him at the time. But for 10-year-old pyjama-clad me, carefully turning the pages of the single surviving author’s copy, they felt like the world.

They still felt like the world as I read them again this summer. Mother had taken good care of them. I was not going to let them sit there any longer, but I was also not going to remove them from where they have belonged all their lives. I scanned them with my phone. Every single page. While everyone I knew in that old city was swimming in the Mediterranean, I was swimming in pages older than I am, with words and lines that shaped who I have become. Seas and rivers appeared in those narratives with abundance anyway.

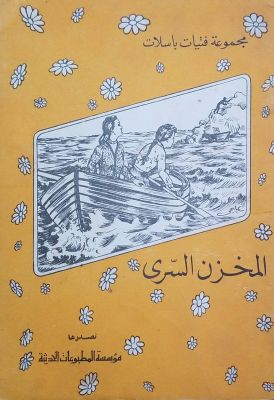

In one novel from a series titled Brave Girls, two girls follow a smuggler in the city of Port Said, by the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean. They take a boat and follow him in the fog to a nearby deserted island where they find out his hiding place and tell the police. In another book from the same series, a girl goes on a sailing trip with her father and single-handedly saves him by standing up to the armed sailors who turn against her family with hopes of stealing her mother’s necklace.

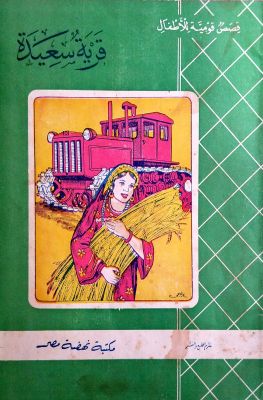

An entire series about young women saving their families and communities. It was published in the 1950s.

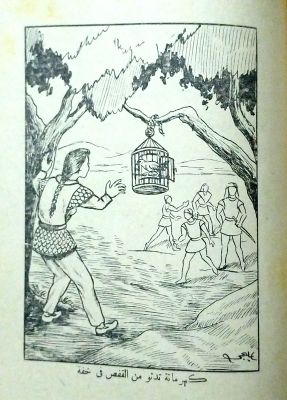

More strong female characters showed up in other stories as I ventured from one genre to another: young adult, historical, fantasy, and folktales. In one Arabian Nights-inspired story, two brothers and a sister are sent by their foster parents to bring a talking bird to the city, a bird that would reveal their lineage to a king. The two brothers fail and are turned into stone. The youngest sister is the one who succeeds. Her name, Kahramana, has lived me with for decades. The key to her success was that she respected a ghoul everyone else tried to either fight or flee from. She simply told it, “Assalamu alykum,” or “Peace be on you,” and waited till the ghoul finished its food. Showing respect.

Respect resonated in other narratives. In one, a shoemaker, Ma’ruf, happily sings and works under the palace terraces of a rich man. The rich man grows jealous of the shoemaker’s peace of mind, a joy that contradicts his obsession with making money. He makes sure Ma’ruf never works again. With nothing but an empty bowl waiting to be filled, Ma’ruf goes looking for a job. He joins a group of sailors. Their boat is shipwrecked on an island and he is the only survivor. Once again, the king of the island is notorious, just like the ghoul. Yet, he is appeased when the stranger who comes to his shores respectfully offers him the only thing he has, the bowl. The king takes it as his new crown and sends Ma’ruf back in gratitude with all kinds of precious stones. The rich man hears of Ma’ruf’s story and goes to the same island, with his own entourage and boxes of expensive gifts, hoping to gain much more for his gifts than Ma’ruf did for an old bowl. The king likes the gifts so much he gives rich man the most precious possession in the island, the crown—Mar’uf’s bowl.

Kahramana and Ma’ruf have represented to me a 10-year-old’s version of bashing stereotypes about the Other. The ghoul and the native king are demonized by the communities of Kahramana and Ma’ruf, but are easily won as friends once the two protagonists choose to see beyond the villainization of the Other. Edward Said went to Victoria College, the same school I went to, only he went a few decades earlier. He would have loved those stories if I could have shared them with him.

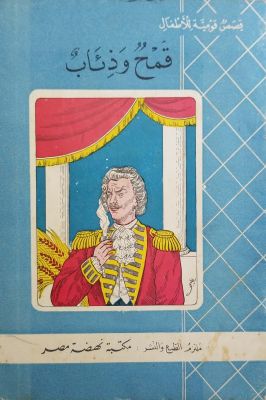

Dazed, I moved on to other books. I met the 6th Century poet Imru al-Qais, known for his erotic Bacchic poetry. In my father’s novel, however, I saw another side of him. The ruler of the Yemeni kingdom Kinda, who is the father of Imru al-Qais, dies. This throws a heavy responsibility on the poet-prince’s shoulders. I saw how the poet transforms into one of the earliest diplomats in the history of classical Arabs, fending for his people against the early colonial powers of Byzantium, the empire that was trying to use local feuds to control the region. This was a superpower ruthlessly employing divide and rule tactics and fighting wars by proxy. Fifteen centuries ago. It did not sound familiar when I first read it by the bedside lamp more than 30 years ago. It is painfully familiar now.

More stories from the 1960s shed light on a politicized cultural shift, from novels that portrayed French colonial atrocities in Algeria to novels that held a dream of class justice, even including a pamphlet with an illustration my father did critiquing British prime minister Anthony Eden.

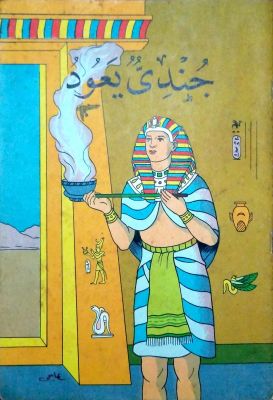

Suddenly, I was greeted by a familiar face. Sinuhe. I have painted him. I have studied him. I have taught his story.

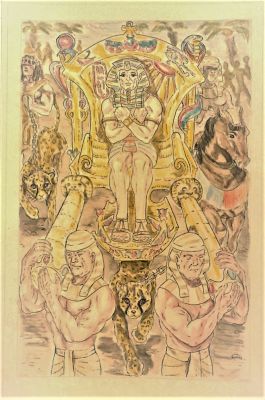

One of the earliest known literary narratives ever, Sinuhe’s Tale tells of loyalty, fear, forgiveness, and honor—but, most of all, it tells of migration and return. A member of King Amenemhat’s court, Sinuhe joins the Egyptian army led by crown-prince Sinusret in the Western desert to fight an insurrection. While camping there, he overhears messengers from the mainland bring classified news to the crown-prince of his father’s death. For no apparent reason, Sinuhe fears for his life and decides to flee. We are never told why he panics. It is left to our imagination to speculate whether Sinuhe and Sinusret had rivalries and the dead king managed to protect Sinuhe from the crown-prince. Or is it that Sinuhe suspects Sinusret of assassinating his father? Or is it, as Mahfouz imagined it, that both Sinuhe and Sinusret are in love with the same princess? We only know that Sinuhe wanders aimlessly until he reaches the North East desert, close to present-day Syria. He settles down with a tribe where he is welcomed by its chief, marries the chief’s daughter and starts a family.

Homesickness, however, does not get old. It festers. Decades later, Sinuhe sends messengers to king Sinusret asking for forgiveness and pleading to be allowed to die in his homeland. Sinusret sends messengers declaring that he has forgiven Sinuhe and welcomes him back. Sinuhe’s return inspired a Mahfouz short story, a novel by Finnish novelist Mika Waltari, and an American film by Hungarian-American director Michael Curtiz. In my little world, too, it has left its impact. It inspired my father and a friend of his to write a novel called The Return of a Soldier. It inspired me to start a graphic novel.

Was it Sinuhe, an immigrant like I have become, who inspired me? Or was it my father’s now-fading brushstroke painting of a smiling Egyptian on the cover of a 50-year-old novel, inviting me to a sleepless summer in Ibn Howqal street, Zizinia, Alexandria, less than a mile from a Mediterranean beach?

Wessam Elmeligi is an assistant professor at Macalester with a PhD in literary theory. He wrote and illustrated two graphic novels, Y and Y (2016) and Jamila (2017), and has published scholarly work on Arabic, American, ancient Egyptian, and Persian literature and art.