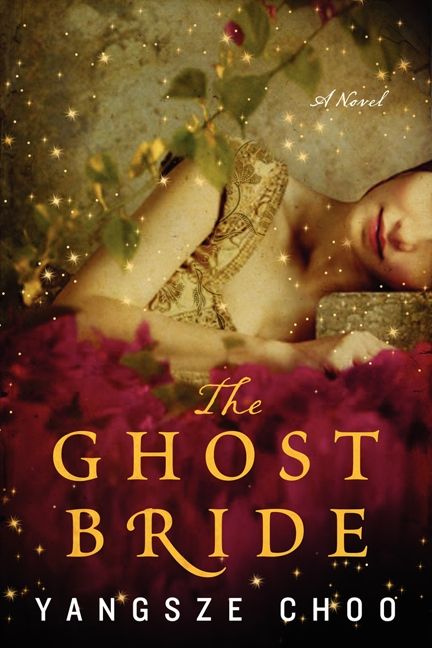

The Ghost Bride and a Scene Told Out of Order

The Ghost Bride by Yangsze Choo is about a young woman, Li Lan, who is being haunted—and courted—by a dead man. After an attempt to free herself of the ghost's unwanted advances, Li Lan ends up a half-ghost herself and wandering in the afterlife—a delightfully bizarre and creepy world of paper houses and bureaucratic terror.

I'm interested in the way the opening moments of the book introduce both the literal idea of a ghost bride, and the upside down logic and atmosphere of the afterlife more generally.

One evening, my father asked me whether I would like to become a ghost bride. Asked is perhaps not the right word. We were in his study. I was leafing through a newspaper, my father lying on his rattan daybed. It was very hot and still. The oil lamp was lit and moths fluttered through the humid air in lazy swirls.

“What did you say?”

My father was smoking opium. It was his first pipe of the evening, so I presumed he was relatively lucid. My father, with his sad eyes and skin pitted like an apricot kernel, was a scholar of sorts. Our family used to be quite well off, but in recent years we had slipped until we were just hanging on to middle-class respectability.

“A ghost bride, Li Lan.”

The first sentence is spectacular. The idea of a ghost bride is intriguing and also what the whole book is about. And the casual way it is mentioned adds something of the uncanny to the opening.

But the second sentence immediately undercuts it. It's a clarification that also serves as a negation. I always think there's a particular intimacy created in moments like this—an intrusive kind. The narrator first invites you to imagine something, in this case a question, but then reaches all the way into your brain to snatch that imagining back. It's a violation of sorts, a nonconsensual entry into the mind of the reader.

And what's more like a haunting than that?

After the image is snatched away, a scene is created. Details of the room and the atmosphere are carefully laid out—the heat and stillness, the rattan daybed, the oil lamp, the opium. There's a ghostliness to many of those details. Moths of course, but also their flutter, the flutter of the newspaper, the act of smoking, the lazy swirls, the humidity. The opium also makes me think of a waking dream—a foggy sense of non-reality that might feeling like a haunting.

But isn't this a bit out of order? Wouldn't we expect to enter the room and learn its description first, before getting the snippet of conversation?

In fact, this sequencing is very unusual in terms of scene-building! Most of the time, at least a few basic details of setting and character are put in place before the dialogue happens. And there's a reason for the convention. Meeting a person before they speak helps us to hear the words. Describing the room first gives context. It all creates a backdrop for whatever happens. In almost every other part of the book, Choo builds scenes in this more common way.

However, It's not just about giving context but about sequence of events. Briefly setting a scene before the action starts gives the feeling of walking into the room and looking around—just as we might do in life. Learning the dialogue before we enter the room disrupts our sense of sequence, an important tool of scene building. Presenting each action in chronological order helps the scene to feel as though it is unfolding in real time and makes the experience of reading the scene more immersive.

So the technique of describing a scene out of order makes the scene a bit less immersive, but it also creates an unsettling sensation—one that I believe is purposeful in this instance.

I mean, obviously, it's unsettling because it's not quite what the reader expects. But beyond that, it's very specifically made to feel like an undoing, like a collapse of a scene rather than a creation. It generates the sensation that we are moving backward through time to learn the lead-up to the father's not-question. Similarly to how the father's not-question is negated, every new detail asks me to re-consider my understanding of what I have already imagined.

And so I'm made to imagine the utterance again, but from a new angle and with this new backdrop. My re-imagining becomes an echo of the father's words. It's not lost on me that we never do get a direct quote of those words or the chance to understand what the utterance was, if not a question. The real words are dead and we only get their shadow.

A backward scene like this one creates a ghost of itself. I don't want to give away too much about Li Lan's subsequent adventure. But as you might guess, the unsettling sensation and the haunting of the reader's imagination set us up remarkably for the strangeness of the afterlife—which Li Lan will enter soon enough.