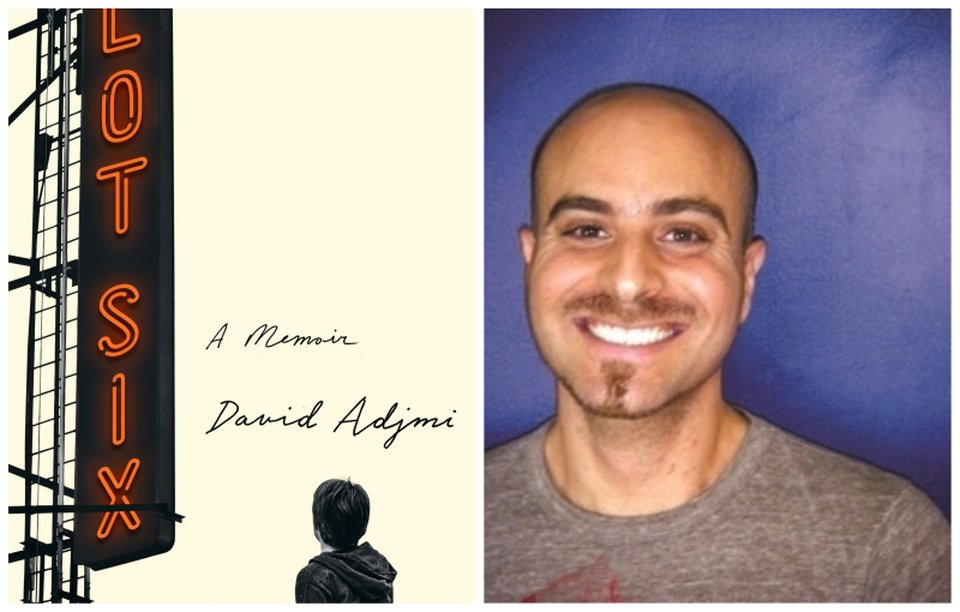

Interview with Author David Adjmi

David Adjmi's debut memoir, Lot Six, explores "how human beings create themselves, and how artists make their lives into art."

For decades now, David’s plays have been produced to critical acclaim, and he’s received multiple prizes, including a Guggenheim fellowship and a Whiting Award. His play Marie Antoinette (2013) received a critically acclaimed world premiere co-production from the American Repertory Theater and the Yale Repertory Theater and a New York premiere at Soho Rep. It was later produced at Steppenwolf and many other theaters across the United States and Europe. His 2018 play Stereophonic will premiere on Broadway next year, with music by Arcade Fire’s Will Butler.

I knew Lot Six was a must-read when I came across a blurb by Melissa Febos. She says, "David Adjmi has written a transfixing, hilarious, and devastating memoir that is wholly unique. Like a match struck in the dark, it set me afire, illuminated aspects of my own self that I'd never faced. It is not often a book possesses this much pain, humor, and power. It is a tremendous artistic achievement and truly one of the best books I’ve ever read."

In this interview, David talks about how he arrived at his vision for Lot Six, how his experience as a playwright influenced and frustrated his writing of prose, and how creative instruction has affected his work and life as an artist.

***

Throughout your memoir, Lot Six, you explore the feelings of displacement from when you were a young kid, being gay in a very homophobic environment, and never fitting in at yeshiva. Was writing about how displacement led to self-invention always at the center of your artistic vision for this project or was it a process to arrive there?

It was a process. Initially I thought I was doing a very different kind of book, something more cerebral. I’d pitched it that way to HarperCollins. I was going to do a bunch of essays about other artists and how their work impacted me. That was how it started. I did write a few of these essays, but I began to feel there was no skin in the game, and it started to become a more conventional memoir, so I just yielded to that. It was probably inevitable that the book became about alterity, because that experience—of feeling like an other, feeling displaced—is so central to who I am in the world. But it was a long tortuous process to arrive at something so fundamental and sort of obvious.

Playwriting and prose writing are such different forms. In playwriting we learn about the characters’ lives mostly through dialogue or monologue and through action; with prose—memoir in particular—exploration of the characters’ interior lives can be more explicit. Can you talk about what you learned through the process of becoming a prose writer? How did your experience as a playwright serve you? What was most challenging?

Honestly, the whole thing very grueling. My editors were nice people, and they meant well, but everyone in publishing is toggling a million things all the time, and no one really had the time to work with me that closely. They’d just say things like, “Oh, this isn’t a book yet. I need to want to turn the page and I don’t.” So I would just go, “Oh, okay!” and skulk home and try to decipher what that meant. It was rough. And writing a memoir makes you an emotional wreck, so I went through extended periods of being very depressed. And it just felt very Sisyphean, working through hundreds and hundreds of pages and finding a way to shape the material so that it tendered a satisfying reading experience—that was extremely difficult.

But if I had to boil it down, there were two huge obstacles I encountered writing this book. First, I am not naturally terribly succinct or orderly in my thinking, so the early drafts were very circuitous and consisted of lots of splatters of interesting things that didn’t necessarily build or go anywhere. I was really earnest in how I approached the process, and I wanted to be “truthful”—but the truth, in prose, is a function of craft. Truth has to be organized and finessed to be communicated, and that requires a specific skill. It took me a long time to figure out how to dovetail the rawness and honesty with things I knew from playwrighting—which is all about structure and architecture. So I’m very grateful for my playwrighting experience, because honestly, I was very deep in the weeds at certain points in the writing of this book, and that stuff saved me.

The second has to do with that issue of interiority you posed. Initially there was almost no interiority in my book. Because yes, in plays—unless you’re O’Neill writing Strange Interlude—writers don’t go into interior monologues and have actors say things like “How dare she slap me? I felt my face get hot. I felt my knees buckle!” and so on. In a play, someone gets slapped, and the actor has some reaction, and then you go to the next scene. It seemed very unnatural to go into these weird interior monologues, but once I added them it changed the momentum of the book, and the feeling of cohesion, and people could finally emotionally connect to the writing. That was huge.

As a playwright, I imagine so much of your attention is focused on character. How did you experience writing the self as character?

Well, I’ve talked a lot about this in other interviews, but I really did not include myself as a character in the early drafts. I saw myself more as a docent or a tour guide through these odd environments with outsized characters. This seemed totally reasonable to me at first. I think Picasso said every portrait is a self-portrait; in my mind, portraiture is a kind of self-revelation. When I write plays, I experience my gaze upon the characters I am writing as content. When people talk about a writer’s voice, they are also speaking about the gaze of a writer, and that gaze is a kind of presence in the writing. So in my plays I am present even if I am not a character—but in a memoir it is not the same thing. Whenever I showed the book to people in those early stages everyone complained that there was no main character. I thought a lot about that. What does it mean to write a memoir with no main character? I started to realize that the self-erasure in the writing mirrored in some respects the content of the book, so I began to inflect that a bit more as a subject: the erasure and construction of a self.

Technically, it was very hard and odd to write myself as a character. The process is hard to describe, it’s a little bit like watching the filaments inside a crystal form and build. I did ultimately have to learn how to walk and chew gum at the same time—meaning I had to be both subject and object as I wrote. It’s like driving a stick shift, you do get used to it over time, but it took me a while to build my instincts around it.

Sharing work in-progress requires a level of vulnerability. You write about how different instructors over the years responded to you and your work as you grew into your self-awareness as an artist. At the University of Iowa, you had instructors who championed your work; at Juilliard, an instructor was cruel and cold. What is the importance of creative instruction and how has it affected you as an artist?

I think what all artists must remember is that we’re the agents of our own destinies. We are the ambassadors of our work. It’s natural to want to look for someone to authenticate what you’re doing, but ultimately you are responsible for your vision, and your politics, and for every single word and piece of punctuation on the page. It’s yours completely. And anyone who wants to subordinate you to some other role in your own writing life—no matter how brilliant they are—is doing you a disservice. The best thing my professors at Iowa did was to show me they had faith in me as an artist, even when the work sucked. They just said to keep going. They made success feel ordinary, and they made failure feel ordinary. They had me embrace the mundaneness of a life as a writer. That was so important. They also understood the peculiar fragility of young writers, and they were careful not to interfere too much in whatever random crisis we were having—because MFA students are generally embroiled in crisis all the time. But they knew when to give us space and let us tussle with ourselves and figure it out on our own.

Lot Six is an amazing exploration of the anguish of building a self, the difficulties and failures and stresses that go into becoming an artist. To make sense of your internal world at times you turn to the external—Fassbinder films, literature, fashion, clinical psychologists, theater. Can you talk about how you used the marriage of the observed and the personal in crafting Lot Six?

There is one section in the book about Hitchcock and the film Rear Window—a film that is all about the gaze, or the juncture between subject and object. For me, the line between watching and being, or observing and becoming, has always been very thin. I grew up in a family where I felt like an outsider, so I learned to communicate by observing and mimicking—and at the same time by repressing my instincts and concealing myself. Art showed me that I could observe and mimic things that would give me access to the stuff I was suppressing. So for me those things you mention—the films and books, etcetera—those were not external, they already lived inside me. Art fleshed out and gave me a vocabulary for who I already was. And when I started to master that vocabulary, I became an artist. I wanted the book to show that process, to show in a very granular way how art and culture can be almost a proxy family.

You say in the acknowledgments that the spirit of New York theater legend Marian Seldes permeates the book. I had the honor of working with her on a production of Harry Kondoleon’s Play Yourself in 2002. Can you talk about the effect she had on your life and work?

Marian and I couldn’t have been more dissimilar. She was this grande dame of the American theatre, and she was a legend. When I met her, I was a floundering student at Juilliard. I’d written this play “for” her, though I never imagined she would do it. But she came and read it in this reading series for the Juilliard writers, and it was great, and I thought that was that. A few months later, I was kicked out of Juilliard, and I sank into a very scary depression. And one day the phone rang, and it was Marian. She’d gotten my number from the literary manager at Juilliard. She’d read another play of mine, and she really got it—which surprised me because it was pretty out there and experimental and kind of dark, but she loved it. We talked for a little while, and at the end of our call she said, “I will always be a part of your circle, and you will always be a part of mine.” She said it in this very poignant way, like it was a torch she was passing to me. I was at a very low point, but she had faith in me.

Years later she gave me a prize in honor of Garson Kanin, her late husband. She came to all my openings. She was just there for me—spiritually, she was there. And this is what I mean about teachers being the bearers of faith. Teachers are people who hold the space for artists to become their best selves. The best teachers are people who see in four dimensions, they see what you could become. Marian was known for being a great teacher of acting. I was never her student, but I consider myself part of her family.

I know you have some history with Minneapolis. When did you live here and is there anything you remember fondly about that time?

I remember it being very cold, and because I didn’t have a car I had to take the bus a lot. I remember the Vietnamese food on Nicollet being absolutely amazing. I lived a few blocks away from Sebastian Joe’s, and I became obsessed with their Raspberry Chocolate Chip—I think that’s probably the best scoop of ice cream in existence. I loved going to the Walker. I loved the art and theatre; there are lots of great, small theatre companies in Minneapolis. I met some wonderful people there, too. This fantastic couple took me in and let me live in their house—their kids were all away at school. They threw these really eccentric parties every Christmas where people dressed in crazy outfits and paid homage to camels. When I think back to my time in Minneapolis, it was like living in a very sweet, slightly kooky small town that was actually a big city. I thought it was really charming.

To learn more about David Adjmi visit https://www.davidadjmi.com/