WTF is a Ballot Boy?: Or How I Found a Home for My Manuscript

On a wet, cold winter day during my third year in Venice, I ducked into the Museo Correr off St. Mark’s Square to warm myself. The vast ballroom Napoleon built in 1797 to celebrate his toppling the thousand-year-old Republic of Venice was empty.

Having been to the Correr many times, I looked for things I hadn’t yet seen. Between one gallery displaying the gold coins each doge minted with his own profile upon election and another featuring “mercymakers,” small daggers with long thin blades to slip into an enemy’s armor for the coup de grâce, a third gallery was almost bare.

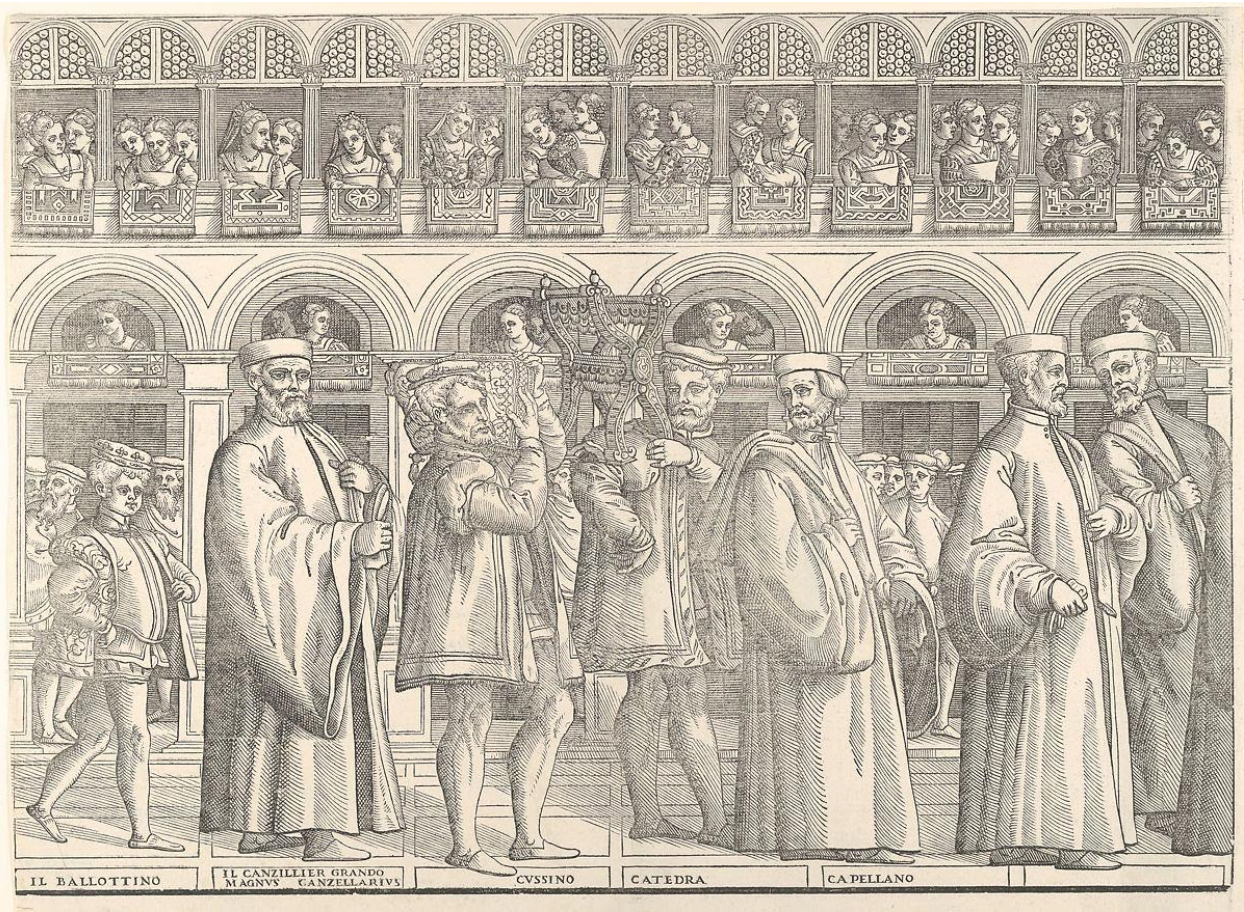

On the long wall fourth wall, eight 17x22-inch woodcuts lined up edge to edge to form a single, continuous image depicting, in meticulous detail, a corteo, the doge’s procession on Palm Sunday in 1556. Like Visconti’s slow pan along the dusty aristocrats seated on carved pews in The Leopard, I moved slowly from the head of the procession to the tail. The procession, hundreds of people long, included musicians, squires, knights, priests, senators, ambassadors, and other nobles of Venice ordered by rank with the doge in the center.

The participants were labeled in Latin. I understood most of the titles, but “Ballottino,” directly in front of the doge, threw me. A kid with a lot of attitude marched between the doge’s stool and pillow borne aloft by squires and the great head of state himself under his gold umbrella. The participants generally made sense to me, but who was the boy strutting his stuff for no apparent reason?

As I pondered the question, a tour group filed into the room, shivering Brits in macs and wellies. I stepped back so they could see better, and the tour guide, who clocked where I was looking, stepped forward, pointed, and said, “This is the ballottino. He counted the ballots in the doge’s election. His job was to keep the nobles honest. He personified innocence and impartiality, so he had to be a boy of common birth under the age of 15, selected randomly to avoid the possibility of favoritism. As soon as he was chosen, he was whisked off to the Doge’s Palace, taken from his family, his pals, his dog, a virtual prisoner personally attached to the doge until the doge died. Fortunately, that usually didn’t take long. They only elected old men for that very reason.”

I was hooked. I needed to know more. And like all things Venetian, the story turned out to be as complex and fascinating as the city.

I stayed in Venice for three more years, researching when I wasn’t teaching English, leading tours, or hosting a bed and breakfast. I dug down deep. Choices had to be made, with 130 doges spread over a millennium. What period? What year? How old was my ballot boy? What happened during his life? I opted for a pinnacle of Venetian history, a brief span encompassing the Black Plague, the beheading of a doge for conspiring to murder all the other nobles, and the Border War with Padua, culminating in the War of Chioggia, the final showdown between Venice and a fatal alliance of her bitterest enemies, the republic’s finest hour. Too much for one book, really, so I broke it out into a trilogy, of which The Ballot Boy is the first volume.

Research and writing ate up a decade, with many tough decisions and about-faces along the way. I count thirteen drafts written to answer the questions: Is it YA or adult? First person or third? Which tense? How historically accurate must I be? Is he gay? Does he have sex? With drafts in every direction, I made my final choices and finished the first “final” draft in 2014. I workshopped that draft at the Loft with Megan Atwood and a group of 15 other writers, garnering tremendous enthusiasm from all. Buoyant after that, I gave my best shot at earning my rejection merit badge. That turned out to be the easy part. By 2020 I was feeling hopeless, having found neither an agent nor a publisher.

Through it all, Sharon Roe, my writer’s group buddy and dear friend, who knew my ballot boy through all his changes, nagged me, reasoned with me, badgered me, and relentlessly encouraged me to keep sending it out. So I did. One more time.

In March, 2021, I blindly submitted The Ballot Boy to Ninestar Press, a small LGBTQ+ publisher. I had given up expecting positive responses and forgot I sent it. Honestly, I sent it to get Sharon off my back. Home from walking my dog one day in mid-April, I found a voice mail alert. “This is Elizabetta from NineStar Press. We’re very interested in your manuscript. I sent you three emails and you haven’t replied so I thought I’d try one more time. We’d like to offer you a contract. Check your spam folder for the emails.”

There they were, all three. God bless her for being so persistent and finally calling me. The NineStar staff is smart, knowledgeable, responsive, and professional. Working with Elizabetta, my editor, has been a dream. She appreciates my ballot boy for all the right reasons and made it a better book.